One out of five pediatric trauma patients treated at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia is likely a victim of abuse.

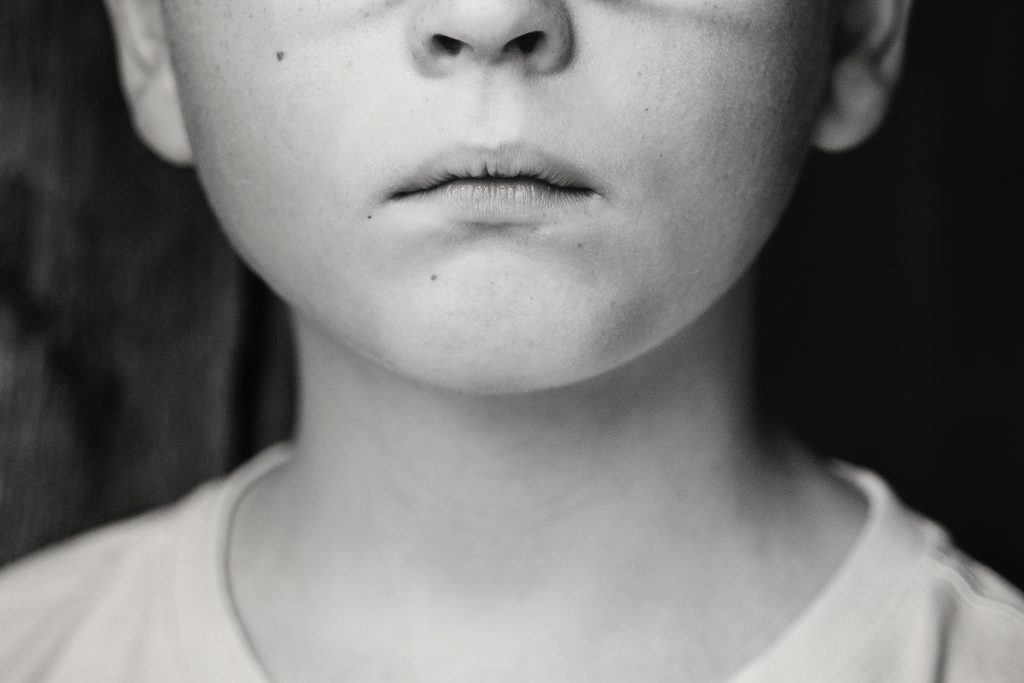

That statistic alone is alarming, but when you put a child’s face to each one of those potential abuse cases, the reality is gut-wrenching.

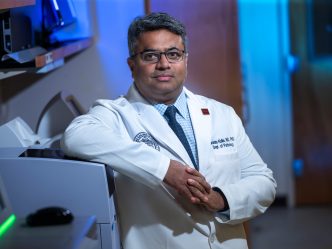

One Augusta University assistant professor and a team at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia are determined to do something about it.

‘It’s devastating’

“Data from the Children’s Hospital of Georgia found that 108 children out of 502 trauma cases involving children were there because of abuse,” said Dr. Melissa Bemiller, an assistant professor of criminal justice and sociology at Augusta University. “So that’s nearly one out of five injured children admitted to that hospital was a result of abuse. After looking at those numbers, I immediately said, ‘We have to do something. We have to look at this further.’”

Bemiller teamed up with Kyndra Holm, the pediatric trauma program manager at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, and Renee McCabe, director for Safe Kids Greater Augusta, to study the alarming number of local children who become victims of abuse.

“It’s astonishing when you look at just how much higher this area is than the rest of the state,” Holm said. “And, unfortunately, we only see the cases of children who actually survive and get to us. Just think of the poor kids who never reach us. It’s devastating.”

Data on child abuse is always a little bit behind, Bemiller explained, but looking at the numbers from the Child Welfare Information Gateway and Kids Count Data Center, Georgia alone experienced a 15.4% increase in child abuse victims between 2012 and 2016.

In 2016, Georgia had 21,635 first-time child abuse victims and 169,323 incidents that resulted in an investigation of child abuse. The 2016 rate of children in Georgia with a substantiated incident of child abuse was 2.3 per 1,000 children, Bemiller said.

Local numbers higher

But locally the cases of child abuse are higher than the state’s rate.

Bemiller looked at data for 15 of our local counties — Burke, Columbia, Emanuel, Glascock, Hancock, Jefferson, Jenkins, Lincoln, McDuffie, Richmond, Screven, Taliaferro, Warren, Washington and Wilkes — which combined make up our Central Savannah River Area of Georgia and our local EMS Region Six.

“Out of our 15 local counties, nine were higher than the state’s rate of 2.3 per 1,000 children in 2016, with the highest being Warren County with 4.3 per 1,000 children,” Bemiller said. “The lowest was Columbia County with 1.4 per 1,000 children.”

In fact, nearly half of our local counties had higher rates of child abuse than the state did for multiple years between 2009 through 2017, Bemiller said.

“And with some of those individual counties, we have seen extremely high rates of child abuse,” Bemiller said. “For example, Glascock County had a rate of child abuse nearly five times that of Georgia’s rate in 2011. Georgia’s rate that year was 2.8, while Glascock County’s rate of child abuse was 13.8 per 1,000. We also saw that Screven County’s rate was four times higher than Georgia’s in 2010, and Warren County was nearly four times higher in 2012.

“Those are clearly outliers, but unfortunately, many of our counties remain at two to three times more than Georgia’s rate from 2009 through 2017,” she said.

“Public data for 2017 is just becoming available,” Bemiller explained, but she has found there was a slight decrease in child abuse for Georgia with a rate of 1.9 per 1,000 children. That’s down from 2.3 in 2016. “Unfortunately, we still saw seven out of our 15 counties with higher rates than our state. Screven County had the highest rate of 4.7 and Columbia County was the lowest at 1.1 per 1,000 children.”

Those statistics are concerning, Bemiller said.

“And these are all substantiated incidents of child abuse, meaning that they were investigated and they were found to be child abuse,” Bemiller said, adding that much of her research over the years has focused on child homicide. “And we know that abuse can lead to murder. So, when I was looking at our child abuse rate, I took it a step further and I looked to see what our area looks like with child mortality, specifically murder.”

Abuse can lead to murder

Homicide was the fourth leading cause of death in the United States for children ages 1 to 9 in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“For the state of Georgia in 2016, homicide was the fourth leading cause of death for children ages 1 to 4 and 10 to 14, regardless of sex and race,” Bemiller said. “It was the fifth leading cause of death for children 5 through 9. In 2017, we saw that homicide increased to be the second leading cause of death for children ages 1 to 4.”

Bemiller looked at child death statistics for the two most populated counties in our EMS Region Six/CSRA: Columbia and Richmond counties.

“In Georgia, the rate of children deaths ages 1 to 14 was 18.7 out of 100,000 in 2016,” Bemiller said. “In Richmond County, it was 43.5 out of every 100,000. That’s terrible.”

Columbia County’s rate was lower than the state’s rate of children deaths, with 17.1 out of 100,000 children.

“While not all of these deaths are homicide, it is important to realize just how high our childhood death rate is in comparison with the state,” Bemiller said. “Looking specifically at children death by homicide is a little trickier considering the numbers are usually so low per county that the data is not released at that level, but we do know that we experienced 35 child homicides in 2016 and 37 child homicides in 2017 within our 15 local counties.”

Augusta-Richmond County had high child homicide rates in both 2016 and 2017, she said.

“Richmond County had the most homicides both years,” Bemiller said. “Now, it’s important to note that not all of these deaths are related to abuse, but research has shown a large portion of childhood homicides may be related to abuse.

“I then decided to ask Kyndra Holm, ‘Can you get me the numbers on deaths that were related directly to abuse?’ The answer: eight out of 10. Eight of the 10 pediatric trauma patients who died at the hospital since Jan. 1, 2017, were directly related to abuse.”

Both Bemiller and Holm were shocked by the high levels of child abuse in this region.

“I looked at it and I was appalled at how many children are affected in this area,” Bemiller said. “The numbers are alarming.”

“I was stunned,” Holm added, shaking her head. “We are here, especially in the trauma program, as a safety net for these kids. And, as the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, we have that responsibility to ensure that we do everything we can to make sure that our most vulnerable kids are safe. It’s just the right thing to do.”

Saving lives by stopping abuse

As a result of her findings, Bemiller decided to apply for a two-year trauma research grant from the Georgia Trauma Foundation, Georgia EMS Association and the Georgia Trauma Commission.

“The call for the grant was basically for trauma prevention, which the statistics show is needed, so I wrote the proposal and was excited to learn that I was one of five awarded the grant in the state,” Bemiller said. “The total grant is more than $260,000. The money is going to be used for a number of things, but predominately it is going to help organize a research team so we can look at child abuse and lethality data from several sources.”

Bemiller expects the project will take about three years and will go in three phases.

“The first phase is going to be data collection from several sources and analysis so that we can get to the bottom of what is going on,” Bemiller said. “Step two is to do a needs-based assessment of the policies and programs that are here in the CSRA directed toward child abuse and child lethality. So that step will include the evaluation of programs. Then, the third step is to create an inclusive, collaborative committee — made up of everyone from law enforcement, nurses, social workers, academics, researchers, and community partners — that can focus on revamping policies and programs.”

While Bemiller is focusing on the local counties for now, she is hoping her work will ultimately help reform other areas throughout the state and even the country that are facing high rates of child abuse and lethality.

“I will be working directly with Kyndra and Renee at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia and they will be the ones providing me with child abuse data from their end,” Bemiller said, adding that they have been designated as program managers. “They are basically my right hand, which is crucial.”

Holm said this will be a great opportunity to help improve the lives of children throughout Georgia and beyond.

“This is amazing. I am floored that Dr. Bemiller received this grant,” Holm said. “For us to be able to have this interdisciplinary connection to use the resources of Augusta University as well as what we do here in the trauma program to really positively impact some local lives is wonderful.”

Giving children a voice

This is research that has been needed for a long time, Holm said.

“I’m really hoping that we’ll be able to piggyback onto Dr. Bemiller’s expertise and help to learn maybe what’s driving our child abuse issues here in the region and why we have such high numbers,” Holm said. “We need to know why we outpace the rest of the state and, therefore, the rest of the nation in terms of child abuse.”

Learning why will lead to ways to help prevent future child abuse, Holm said.

“I would like to be able to tailor some of our prevention efforts to help keep these kids from getting hurt in the first place,” she said. “After all, a big part of our job is injury prevention. We would much rather prevent somebody from ever getting hurt in the first place than treat them after the harm is done.”

As part of the grant, Bemiller is also planning to have some of her department’s students’ help with the project’s research.

“There will be two designated student helpers who will have research-oriented responsibilities specifically helping with this project. Additionally, I plan to have other students involved through class work activities,” she said. “I think it’s very important to get our students involved in this project because this is going to be a very wide community-based project.”

Holm said she is grateful Bemiller is willing to commit to such emotionally difficult research regarding child abuse.

“She’s able to pull everything together from more of a criminology and public health standpoint,” Holm said. “Then, we can take that information and hopefully translate that into programs that will help go into the community and prevent child abuse.

“If we can do that, it would just be life-changing. Just think about all the kids who could grow up to have a productive adulthood who may not have ever had that chance.”

Helping children escape or avoid abuse has always been the driving force behind her research, Bemiller said.

“I have spent 10 years researching childhood abuse, lethality and injury prevention,” Bemiller said. “My main priority is the children in our community. I want to help give these children a voice by assisting in discovering risk factors and correlates and formulating proactive strategies to help combat this increasing problem.”

Augusta University

Augusta University