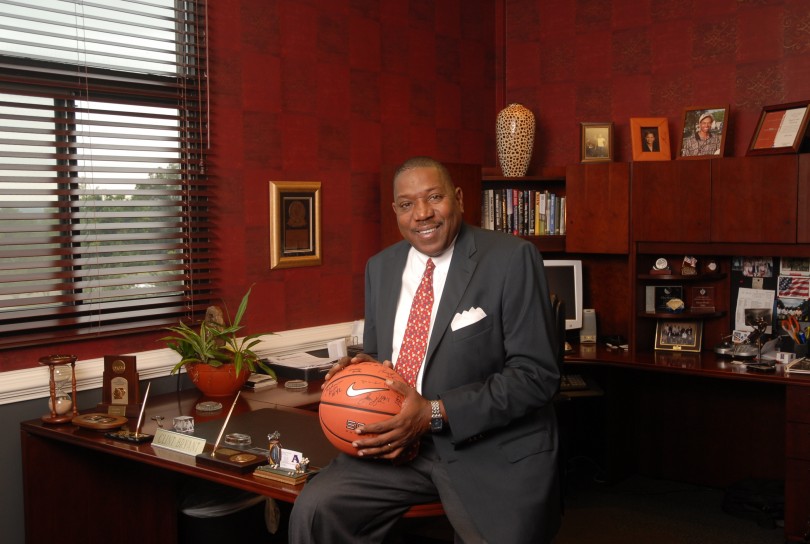

Growing up in Elberton, Georgia, Marcus Allen had a lot of incredible teachers who inspired him to be the man he is today.

They were thoughtful, patient and caring, but Allen, who is now the principal of Grovetown Middle School in Columbia County, admits there was one major component missing throughout his childhood education.

“Back then, I didn’t see people who looked like me teaching,” Allen said. “I didn’t have any African-American male teachers at my school. And I think it’s important for students to be able to see someone who they can relate to in the classroom. Somebody who they can say, ‘He really might be able to advocate for me.’”

Allen, along with local teacher Clarence Kendrick, will be speaking in partnership with the Augusta University College of Education on “Minority Males Transforming Education.” The event is at 7 p.m. Monday, Dec. 2, at the Academic Success Center on the Summerville Campus.

This discussion is part of the African-American Male Initiative (AAMI) program’s Man Cave Monday series this fall. AAMI is a statewide initiative designed to increase the number of African-American males who complete their postsecondary education from any of the 26 University System of Georgia’s institutions.

In addition, the College of Education is planning to host a summit for minority male educators on March 30, 2020, in the ballroom of the Jaguar Student Activities Center.

College of Education Dean Dr. Judi Wilson has teamed up with Coach Clint Bryant, the director of athletics at Augusta University, to address the absence of racially diverse educators in both primary and secondary classrooms.

Recent data from the National Center of Education Statistics (NCES) estimates that since 2014, ethnic and racial minorities make up more than half of the student population in public schools across this nation, yet people of color represent about 20 percent of the teachers and only 2% are African-American men.

In fact, this fall in the College of Education at Augusta University, there is only one African-American male student teaching candidate of the 50 candidates in the program, according to Dr. Kristy Brown, the director of assessment and accreditation at the College of Education.

The benefits of diversity in teaching have long been known. Studies show that teachers who instruct students of the same race are more likely to discipline equitably, to set high expectations and to recognize student achievement, according to the National Education Association’s 2014 study, “Time for a Change: Diversity in Teaching Revisited.”

“Educators who are grounded in the day-to-day experiences of their students and communities bring to their work more favorable views of students of color, including more positive perceptions regarding their academic potential,” the study states. “They frequently teach with a greater level of social consciousness than do others, appear to be more committed to teaching students of color, more drawn to teaching in difficult-to-staff urban schools, and are more apt to persist in those settings.”

In particular, African-American students who have an African-American teacher in elementary school are more likely to graduate high school and attend college, according to the article, “The Long-Run Impacts of Same-Race Teachers,” published in 2018 by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dr. Kenneth Bradshaw, the new superintendent of Richmond County schools, has agreed to join Augusta University’s task force that will discuss this national problem at the March 30 summit. Allen and about a dozen other local African-American educators have also been asked to participate.

The power of mentoring

As a graduate of Augusta University’s Class of 2002, Allen said he has learned over the years that teachers mentoring other teachers is the key to success.

“During the three years that I worked with Principal Michael Johnson at Evans High School, he taught me so much,” Allen said. “He told me, ‘You should always be doing one of two things: mentoring someone or being mentored. And when you’re really in a good place, you’re doing both. You are being mentored and you are mentoring someone.’”

Allen said he took that advice as a personal challenge to help anyone who wants to go into a leadership or teaching position in education.

“I want people to understand that education is a lot more than numbers and books. It is really about people,” Allen said. “We are in the people business. And I tell my teachers all the time, words matter. I want teachers who know how to talk to people.”

Regardless of gender or ethnicity, Allen said it is crucial for teachers to be able to relate to their students.

“You have to recognize that the student is another person. That is someone’s child and how I speak to that child can dictate their day,” Allen said. “And no matter how they are behaving in class, their response can’t dictate ours. When they are upset, we are the professionals. They are the child. So, I really just encourage teachers and tell them that words absolutely matter.”

The way a teacher relates to a student is so important to Allen that he incorporates that interaction as part of his interview process when recruiting new teachers.

“When I interview people, I want to know how they treat people,” Allen said. “So, when teachers come in for an interview, I bring a student in and say, ‘Hey, this is Johnny. Get to know him.’ I want to see how you interact with that child.”

Many candidates are caught off guard by this approach, but Allen said it helps him see how a teacher might behave in a classroom.

“They are always kind of shocked,” Allen said, laughing. “They are like, ‘Wait a minute,’ but that’s what I care about the most. Can you relate to that student?”

After all, teachers can completely change a child’s life, Allen said.

“I had a teacher in Elberton named Mrs. Shawn Rivers,” Allen said. “She was my 12th grade English teacher. She is now an assistant principal at Elbert County High School, but she made a huge impact on my life.”

Rivers refused to accept excuses when it came to classwork, he said.

“When I was growing up, I didn’t have a whole lot at all,” Allen said. “And I remember using that as a crutch. I would tell teachers, ‘Well, I don’t have a dictionary at home, so I can’t complete that assignment.’ And I remember Mrs. Rivers saying, ‘That’s not an excuse. That’s a reason, but it doesn’t excuse it.’”

She saw he needed help and reached out to him, but didn’t give him a free pass, Allen said.

“That was the first time someone really held me accountable and didn’t allow me to use my background or situation as an excuse,” Allen said. “I never forgot that. She changed my life.”

A born teacher

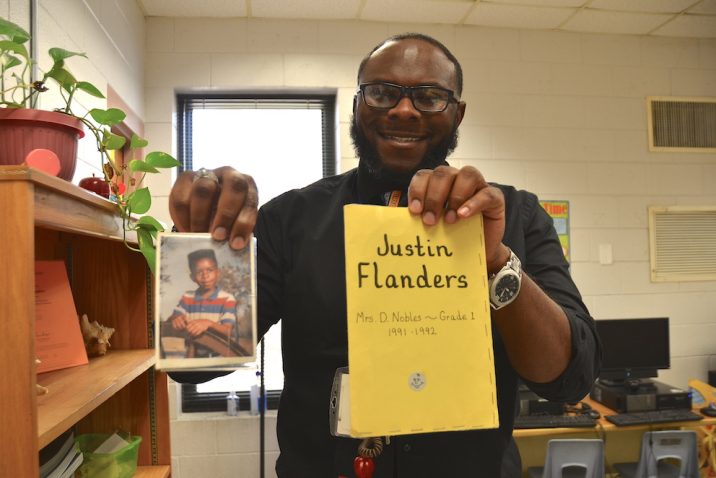

Justin Flanders, who graduated with his bachelor’s degree in 2010 and his master’s degree in 2014 from Augusta University’s College of Education, always knew he wanted to be teacher.

“There was never any doubt in my mind,” said Flanders, who teaches first-graders at Tobacco Road Elementary School. “My aunt was a teacher and I lived with her, so I have been grading papers probably since I was in the second grade.”

He had such a passion for teaching that his father, who was a construction worker, actually built him a schoolhouse in the back yard.

“We always played school in the neighborhood, so when I was in the third grade my dad built me a block house with a walk-around chalkboard behind our house because he knew I wanted to be a teacher,” said Flanders, adding that he grew up in Soperton, Georgia. “So, in the afternoons, I would teach the neighborhood kids. I would give them worksheets from the Highlights magazines and that would be our assignments.”

Flanders decided to enroll in Augusta University because his sister was already a student at the college. And, while he never doubted he wanted to be a teacher, it took guidance from a professor to steer him toward elementary education.

“I knew that I wanted to teach, I just didn’t know what I wanted to teach,” Flanders said, explaining that he considered teaching history and then science, but always got bored with teaching just one subject. “Finally, one day, Dr. Charles Jackson from Augusta University said, ‘Mr. Flanders, you should try elementary education. That way, you’ll be able to teach every subject.’ I tried it and I’ve been here ever since.”

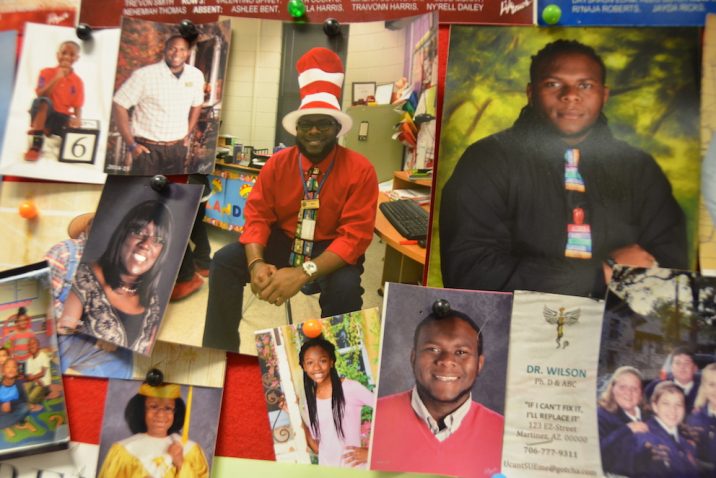

For the past 10 years, Flanders has taught at Tobacco Road Elementary School and enjoys inspiring younger children to embrace education.

“These kids are eager to learn,” Flanders said. “At this age, they aren’t really defiant. They want to learn and it is very funny the things that they say. They are very truthful. Kids will let you know exactly what they are thinking.”

The keys to being a successful teacher are patience, flexibility and open-mindedness, Flanders said.

“You can’t have a closed mindset and you have to be engaging because some kids, if you are boring, they are going to go to sleep and they are not going to listen to you,” Flanders said. “So, I just can’t stand up there and talk all day. I have to put my lessons in a rap or a dance. And, with these kids, I can be goofy, I can be myself and I can put on a show and they are going to love it.”

To better relate to the students, Flanders, who was Tobacco Road Elementary’s Teacher of the Year in 2017, said he even shows the children his report card and class photo from the first grade.

“I want them to know that I’ve been where they are,” Flanders said. “I understand what they are going through.”

In addition, Flanders also participates in the school’s Guys and Ties program to encourage boys to behave like young gentlemen.

“We have this club called Guys and Ties where we mentor the boys. So, on Tuesdays, we dress up and wear our ties,” Flanders said, holding up his colorful tie. “So, you will see the young kids with their ties on Tuesdays and we teach the boys how to treat ladies. We teach them how to hold a door open and be respectful.”

It is remarkable how much students respond to positive attention, Flanders said.

“Those kinds of things are important because a lot of our kids don’t have that male role model in the home,” he said. “So, when they see me, they know I am here to help.”

Returning home to teach

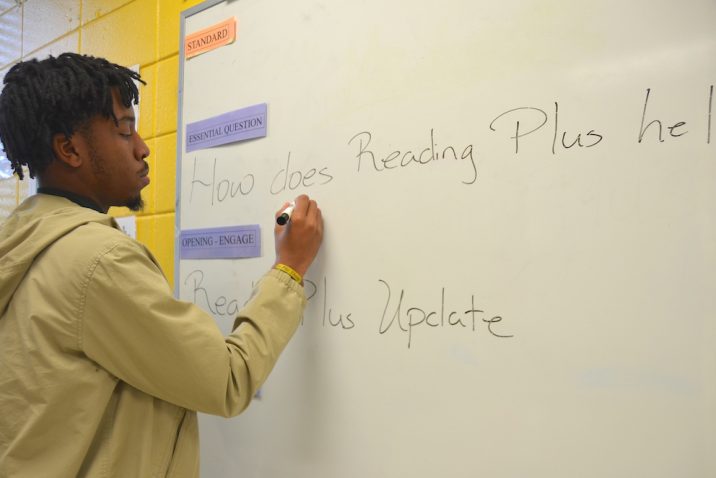

When Tom Aaron Bennett Jr. looks around his seventh-grade classroom at W.S. Hornsby Middle School, he can easily put himself in his students’ shoes because he grew up in east Augusta and attended the very same school.

“I had a teacher here named Mr. Jerry Hunter. He’s at Westside High School now,” Bennett said. “I remember when he was interacting with the kids, he was always willing to listen. He had a listening ear and he constantly told us, ‘No matter what you are doing, put your best foot forward.’”

While Bennett was inspired by Hunter, he admits he never considered becoming a teacher when he was younger.

After graduating from Lucy Craft Laney High School in 2011, Bennett attended Savannah State University and received his bachelor’s degree in English with a minor in Africana studies.

Then, one day, a friend suggested that he should consider teaching.

“I was like, ‘I don’t know about that,’” Bennett said, laughing. “But I started talking to different people and they said, ‘Yeah, you should try it.’ So, I came back to Augusta and started out as a substitute teacher for a semester.”

Bennett taught at several schools throughout the Richmond County School District that first semester.

“That was pretty eye-opening,” Bennett said. “I realized, for the most part, that all of the students are kind of the same. And as long as you are teacher that listens to them, you can be a good teacher and they will grow to love you.”

Bennett, who is currently seeking his master’s degree from Augusta University’s College of Education, is now in his third year as a teacher at Hornsby Middle School.

“My first year as a teacher, it was definitely challenging, but I can say it’s worthwhile,” he said. “I think many students can see themselves in me. And I think because I’m from here, I have more passion for them to succeed, so I am going to push harder.”

Students in his classroom see him as a part of their lives now, Bennett said.

“It’s is amazing how students will try to connect with you, even though I’m just a teacher,” Bennett said. “They want me to come to their games. And I’m not talking about just games at Hornsby, but I’m talking about games with the recreation department.

“They want my time. They will say, ‘Mr. Bennett, are you coming to see our practice?’ Because, once they see that you care and you love them, they want your support in different realms.”

By providing that extra time and support, students respond better in the classroom, Bennett said.

“If I go to their practices or I go to their games, that’s not only a conversation starter, but that’s a reminder that, ‘Look, I was at your practice, now. You can’t be bad at practice and in the class,’” Bennett said, laughing. “If I support them, I can make jokes like that and they will say, ‘You’re right, Mr. Bennett. You’re right.’ And that kind of gets them going and back on track.”

Bennett said good teachers must have a lot of dedication.

“Teaching is one of those jobs that you can’t leave it at work,” he said. “You are going to go home, grade papers, do lesson plans and call parents. The job doesn’t stop at 5 o’clock.”

But his secret weapon is always having a “listening ear,” Bennett said.

“You have to be willing to listen to a kid, even though you might be busy and have a bunch of stuff going on because you might be the only person who actually listens to them,” he said. “You never know, you might save their life. You might be the one person who is keeping them going. So, you have to be there for them and really listen.”

Augusta University

Augusta University