A test that looks at the genetic expression of breast cancer cells to assess the 10-year recurrence risk and help physicians and patients make more selective treatment choices is now available at the Medical College of Georgia and the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University.

The Prosigna™ Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature Assay will help clarify the recurrence risk – and the need for chemotherapy – in postmenopausal women with earlier stage, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

The test is the first and only prognostic test for breast cancer using an available sample taking during surgery that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Augusta University is among the first eight academic institutions in the nation to make the test available to women and their physicians.

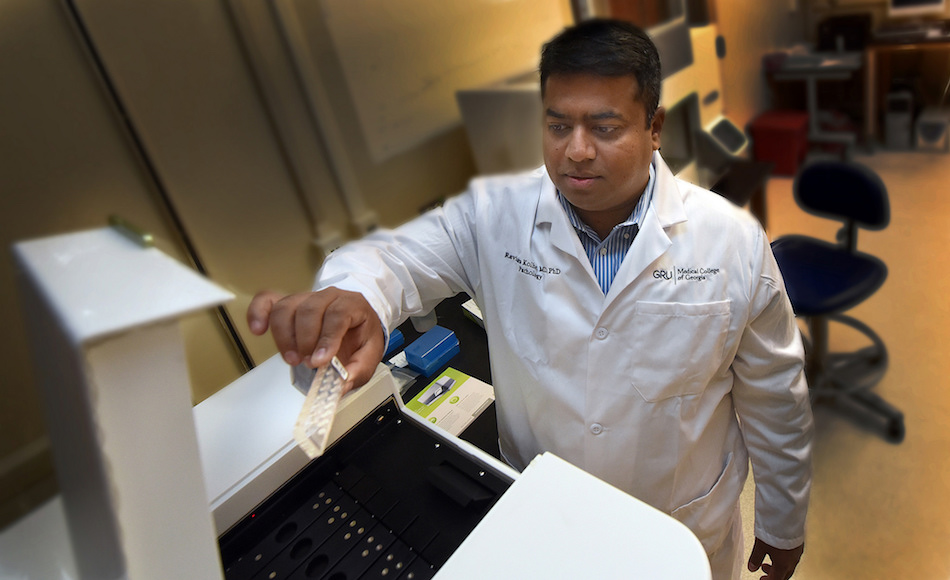

“Improved screening means we are finding more breast cancer at an earlier stage and we end up with this conundrum: Do we give these patients chemotherapy or not,” said Dr. Ravindra Kolhe, breast pathologist and director of the Georgia Esoteric & Molecular Labs LLC in the MCG Department of Pathology. “This is a national discussion.”

After surgery to remove the tumor, typically, pathologists measure its size and look at cells under the microscope. Aggressive tumor cells tend to be poorly differentiated, resembling a sort of “tumbleweed,” while less-aggressive cells look more like healthy breast cells, Kolhe said. Factors such as the patient’s age and other medical problems also are considered.

“Based on microscopic examination alone, it is difficult to clearly tell clinicians which patients need chemotherapy,” he said. The new test can better stratify their low-risk versus high-risk status.

Currently, the tendency is to err on the side of caution and give some type of chemotherapy to everyone, Kolhe said. Helping even a minority of patients instead avoid what is essentially unnecessary treatment is the biggest benefit of the new test, he said. He notes that the new test will not replace any of the existing pathological studies on these women.

With the next test, MCG pathologists take cancer tissue removed during surgery and look at the expression of 50 genes differentially expressed in women at high and low risk of breast cancer recurrence within 24 hours. “If the aggressive genes are expressed more, you know there is going to be a recurrence,” Kolhe said.

“Chemotherapy is good for preventing recurrence but it can have extreme side effects,” Kolhe said. “We want to make sure that patients who don’t need this treatment don’t get it, and, of course, that those who do need it do.”

Chemotherapy preferentially attacks rapidly dividing cells, such as cancer cells, but also can impact a number of healthy, fast-dividing cells such as those in the bone marrow, the digestive tract, reproductive system and more.

The sex hormones estrogen and progesterone have a role in the growth and function of healthy breast cells. The majority of breast cancer cells also have receptors for the hormones and use them to aid their growth and survival. Regardless of the findings of the new study, essentially all women with hormone-receptor-positive cancer will continue to receive hormone therapy, such as tamoxifen, to interfere with the growth signals being sent by hormones and leave cancer more vulnerable.

Augusta University

Augusta University