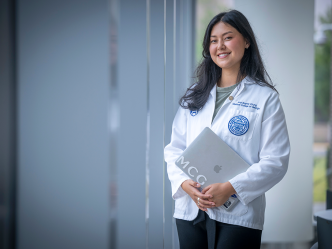

Sehar Ali’s first patient at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University was an 80-year-old physicist.

Outside of his age, his physical appearance and a brief description of his profession, she knew next to nothing about the man — not even his name. Only that he was recently deceased. He’d left her, it seemed, nothing but questions. Was he a father? A son? A brother? Was he satisfied with the life he had lived or did he, in the final moments of his life, feel regret for things he had yet to accomplish?

Only those who loved him would ever know.

However, during her time in the anatomy lab at MCG, a course and experience every first-year medical student undertakes, Ali learned things about the man that he likely never knew himself. She studied his aches. His pains. The minute inner workings of his body, the structures and pathways unique to his genetic blueprint. The experience left her with an indelible memory. It also instilled in her a never-ending gratitude.

“Working with my body donor was one of the most rewarding experiences I’ve had in medical school,” she said. “It was such a gift to be able to learn about the human body by exploring it myself.”

Like many students new to dissection, Ali wasn’t always eager to learn from the deceased, though. She expressed her reluctance to her tour guide during her interview tour of the college. She had never worked with cadavers before, and the thought, if she were being honest, made her more than a little apprehensive. Her tour guide, himself a medical student, understood her concerns. He also knew just what to say to assuage them.

“Before walking in, he told me about how the body donors are more than just cadavers — they have stories and families,” she said. “He said that his body donor was his ‘first patient,’ and that after he was done working with him, he wrote him a letter of gratitude.”

That bit of wisdom stuck with Ali. So, too, did the tradition of writing notes to body donors.

While the casual observer might find it morbid, the act of thanking body donors is a sacred right of passage for many medical students. So intricate are the structures of the human body that working with a cadaver is often a student’s first introduction to the reality of modern clinical care: Everybody — and every body — is unique. There is no such thing as a “cure all,” because there is no “all” in medicine. That realization, Ali said, was an invaluable insight to take with her into her medical career.

“Engaging in this kind of hands-on learning, we’re now able to visualize each structure and the pathology associated with that structure more clearly,” she said. “That’s something that can only be taught by having an experience with a body donor. It cannot be taught by a textbook or a mannequin.”

Hunter Parmer, a fellow second-year medical student, had a much different experience with anatomy. Having previously worked in hospice care, he was accustomed to working with patients at or near the end of their lives. In fact, he welcomed the chance to learn more about the body’s inner workings, reveling in the challenge.

“The whole semester, we’re sort of like detectives,” he said. “We’re given a task to determine how we think this patient died. It’s usually something wildly different than what you’d think.”

Parmer, too, learned about the tradition of writing notes to cadavers early in the semester. He and his fellow groupmates also wrote notes to their “first teacher.”

“It was another chance to thank my cadaver for the things he had taught me,” he said. “For being my first patient.”

The act of dissection can be a deeply emotional experience. From the outset, students understand the cadavers they are learning from were once living people, individuals with their own loved ones, their own personalities, their own hopes and wishes for the future. Even so, studying certain structures can have a profound impact on young learners. For Ali, the moment came when she and her groupmates reached her cadaver’s hands.

“At one point during the session, I began holding his hand so that my peer could find a structure on the dorsum of the hand,” she said. “I started to think about how I used to hold my dad’s hand when I was younger; I’d hold them when I was happy or sad or scared.”

Holding her patient’s hand, she couldn’t help but wonder what kind of memories they had been a part of. That her donor had trusted enough in the educational mission of the college, in the education of future doctors, to entrust his own body spoke volumes about the type of person he was.

“It was a very humbling experience to know that he and his family trusted us to learn from him and, in a way, allowed us to be a part of his story on Earth,” she said.

Parmer, who had a similar experience when working on his cadaver’s face, said it isn’t uncommon for students to get emotional during their anatomy courses.

“I guess this,” he said, steepling his fingers, “is for a lot of people the defining aspect of being human. That we can grasp things, manipulate things. It has an impact on people, coming to that realization.”

Parmer, who said he’s interested in possibly working as a surgeon, said the most incredible aspect of anatomy was dispelling the idea of “normal” when it comes to bodily structures.

“Every body is different; there’s so much variation,” he said. “When you’re looking at a model or a picture, you know, that’s the ‘average’ structure. But the main circulatory flow to the brain, the ‘average’ of that is only found in about 15 percent of the population.”

Before anatomy courses begin in earnest, incoming students participate in a ceremony honoring the generous dead and their sacrifice. A similar ceremony follows the end of each semester, a group “thank you” commemorating lessons learned. After this ceremony, students so inclined write notes to their cadavers — their first patients. The content of these notes is private, known only to the students. After writing one, students tuck them into their cadaver’s covering shroud and body bag to be cremated, a final secret farewell, and for many, a final well wish.

“If I could say one last thing to my patient, it would be an infinite thank you,” Ali said. “It’s impossible to put into words how his sacrifice has impacted me and my fellow peers.”

All donors to the MCG Anatomical Donation Program are honored during an annual, non-denominational Memorial Service held in November of each year. Many of the students who worked with donor cadavers participate, singing songs, playing music, or reciting poetry to honor their first patients’ loved ones. For many, the experience is an emotional capstone to the semester — and a reminder for the future.

“This experience has helped me understand the need to treat each patient with respect,” Ali said. “When our donors gifted their bodies to science, they exemplified compassion and selflessness. It is our duty as future physicians to learn this from our first patients, and in turn, to treat each patient after them with the same compassion and selflessness.”

Augusta University

Augusta University