Born with the heart condition tricuspid atresia, Angela McGahee wasn’t expected to survive to see adulthood. But she defied all the odds. She was strongly advised to never get pregnant due to the extreme risks involved, but with the help of her doctors at the Medical College of Georgia, she became the first woman with tricuspid atresia to ever deliver a healthy, full-term baby. Not only was she a loving and devoted mother to her son, T.J. Smith, but she also proudly became a grandmother to her grandchildren, William and Savannah. Her passion for life was contagious, her family says. While she sadly passed away on Sept. 17 at age 54, her courage and strength will never be forgotten. This is her story.

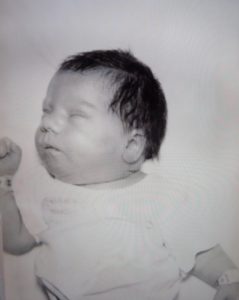

As soon as Angela McGahee was born on May 7, 1966, at St. Joseph Hospital in Augusta, the nurses and doctors immediately realized something was terribly wrong.

“From the day she was born and they laid her in my arms, I knew I would have to fight for her life,” said her mother, Threesa Hood, from her home in Dearing, Georgia. “They told me something was wrong with her, and I remember I couldn’t even see her through the tears in my eyes. I didn’t even know what she looked like because I was crying so hard.

“But, from that day forward, I willed her to live. I would not accept anything else. That’s all there was to it. I willed her to live.”

Doctors informed Hood that her infant daughter had a heart defect called tricuspid atresia. This defect does not allow venous blue blood (less oxygen) to flow to the lungs through the upper and lower chambers of the right side of the heart because of a blockage between the upper and lower chambers.

Therefore, Hood’s baby wasn’t getting enough oxygen through her body and she was known as a “blue baby.” The doctors immediately knew Hood’s child was suffering from this condition because she had shortness of breath and blue-tinged lips. Until the mid-1970s, there was no way to correct this condition, although it could be partially palliated.

“I can’t tell you the times that I cried and cried holding her,” Hood said. “When she was a baby and I would lay on the bed with her, you could hear the blood rushing through the holes in her heart.”

As an infant, Angela was evaluated by doctors in Augusta at the Talmadge Memorial Hospital, which was subsequently renamed the Medical College of Georgia Hospitals and Clinics.

“I remember taking her to Talmadge Hospital when she was 11 months old and, of course, the more they checked her, the worse they told me things were,” Hood said, adding that the doctors told her Angela would eventually need heart surgery. “But, despite the news, she surprised them all because she ran around and played like nothing was wrong with her.

“In fact, they didn’t believe me when I told them that she played and went to school and did all the things like a regular child. But she did. She never, ever once in her whole life complained about her heart or being tired.”

Strengthening Angela’s heart

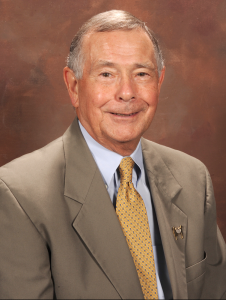

Dr. William Strong, a pediatric cardiologist who joined the Medical College of Georgia’s Department of Pediatrics in 1969 and became chief of Pediatric Cardiology in 1972, remembers meeting Angela and her mother in the early 1970s.

“We followed Angela medically and diagnostically with catheterizations until a procedure became available that could prolong her life,” Strong said. “At that time, the average life expectancy of a patient with tricuspid atresia that was palliated was about 15 years.”

When Angela turned 12, the family was told to prepare for the fact that she needed to have open-heart surgery.

“Making that decision was just about to kill me, but they called me one day and they said, ‘We’ve decided we can wait a while on Angie’s surgery,’ so they did. They waited a year and then they called us in the office and they said, ‘It’s time. We can’t wait any longer,’” Hood said. “So, by then, that wasn’t a choice that I had to make. There was no doubt that she needed the surgery, so I told them they could do it.”

Cardiologists at the Medical College of Georgia explained to Hood that her daughter required a Fontan procedure. The goal of the original Fontan procedure was to take venous blood from the upper and lower body and have it become oxygenated by connecting a portion of the right atrium, the upper chamber of the right side of the heart directly to the pulmonary artery that carries blood to the lungs to become oxygenated, or red, Strong explained.

Thus, by means of the Fontan procedure, it was possible to eliminate the venous blood from entering the circulation to the body, resulting in the patient becoming “pink.” The initial results of the Fontan procedure suggested a prolongation of life into the third decade, Strong said.

“With Angela, only one of the two pumping chambers of her heart were present. Therefore, the pumping chamber sent out both the red and blue blood, the oxygenated and unoxygenated blood, to her body,” Strong explained. “She was initially helped by having a shunt procedure performed that increased her oxygen in the blood. But when this Fontan procedure became available, then her defect was more appropriately corrected so that all of the blood from the right side of the heart went directly into her pulmonary artery, which took it to her lungs to get oxygen.”

But the doctors told Hood the Fontan procedure was a complex surgery with a number of risks.

“That was a very hard thing to decide, to take your child out of school and hand her over to the doctors when they give you all these different percentages about the risks involved with the procedure,” Hood said. “You must realize, the Fontan procedure was new back then, so that was really scary.”

After the family agreed to the surgery, Hood remembers Dr. Syamasundar Rao, who was Angela’s cardiologist at the Medical College of Georgia at the time, walking into the room to reassure her that she had made the right decision.

“I will never forget it. Dr. Rao came into the room and said, ‘Mrs. Hood, don’t pay any attention to those percentages. It doesn’t matter if it’s 99-to-1. If you’re in the one, then you are in the one, so don’t listen to the percentages,’” Hood said. “He gave me faith that everything would be all right.”

Hood said that Angela, who only weighed 78 pounds at the time of the surgery, was on a heart and lung machine for approximately nine hours. When the family was finally allowed in the recovery room following the surgery, Hood recalls some of her relatives couldn’t handle seeing Angela connected to the machines.

“My sister was just so upset when she looked at Angela after the surgery that she ran downstairs and got sick. She couldn’t take it. But when I looked at Angela, all I saw were pink lips,” Hood said, smiling. “I thought those pink lips were the most wonderful thing in the world because that meant she was getting the oxygen that she had not gotten before.

“So, I didn’t pay any attention to all the wires and tubes. Her little lips were just as pink as they could be and, to me, that was truly beautiful.”

A new life emerges

Angela had to stay in the hospital for several challenging weeks to fully recover, but once her body began healing, her daughter was back to her old self, Hood said.

“She was an active child, who loved going on trips to the mountain or the beach and she absolutely adored Disney World. I bet we went to Disney World more than 40 times,” Hood said, laughing. “She also loved roller coasters. When we’d go to Disney World and Universal Studios, she insisted on riding every roller coaster there was. You couldn’t drag her off a roller coaster.”

During one of Angela’s doctor visits as a teenager, Hood remembers Strong speaking frankly to her daughter about the future.

“She was a young teenager and Dr. Strong looked right at her and told her, ‘Now, if you ever decide to get kissy face with any boys, you come talk to me,’” Hood said. “I remember that day because I didn’t think she could get pregnant. The doctors always said she can’t get pregnant. Well, I thought they meant, physically, she couldn’t get pregnant. I was wrong.”

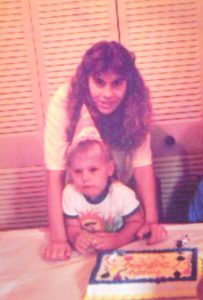

Not long after getting married and moving to Alabama, Angela returned to Georgia with some news for her mother.

“She called me and wanted to come home. We had some land available, so we put a trailer on the property for her,” Hood said. “When she got here, I found out she was pregnant, and I was beside myself. I was truly devasted.”

Hood knew the doctors had said it was too risky for Angela to attempt to have a baby and it would likely result in both her and the child’s death.

“I remember I was so upset and I said, ‘That’s it. You’re having an abortion. This is not going to kill you,’” Hood said. “Now, you must understand, I don’t believe in abortions. Not at all. But I was trying to save my child’s life, so we went down to the hospital and they did a sonogram.

“I remember the baby opened his little hand and closed it. That was it. There was no abortion in the picture. She was in love with that child and she was keeping the baby.”

When Strong heard that Angela was pregnant, he was immediately concerned.

“Since no woman with her diagnosis had ever, as far as I could ascertain from the literature, become pregnant and delivered a typical, full-term baby, I had recommended that she not become pregnant and gave her all kinds of options,” he said.

“But as things happened, she became pregnant and elected to carry the baby. To my amazement, she did so without any complications, whatsoever. It was just an incredible feat.”

Despite her heart condition, Angela, who was 21 at the time, remained strong throughout the pregnancy, he said.

“She was a true hero,” Strong said. “She had the courage to carry the baby to full term. At that time, most physicians would have recommended that she have a therapeutic abortion. But that was something that she did not want. She had the courage to say, no. She wanted to have her baby, regardless of the risk to her.”

And the risk to a mother with tricuspid atresia was exceedingly high, probably greater than 30% mortality, Strong said.

“When she finally got to term, she delivered a full-term, big baby. Her son, T.J., weighed something in the range of nine pounds or so,” Strong said. “So, it was a chore for her to just carry him around. But she had T.J. and continued to be followed by us in pediatric cardiology and as an adult in our congenital heart disease clinic. She did very well and had only minor problems over the years.”

Hood said Strong’s support of the entire family meant the world to Angela.

“She loved him dearly,” Hood said, smiling. “She used to tell people, ‘Dr. Strong is my other daddy.’ He always took great care of Angela.”

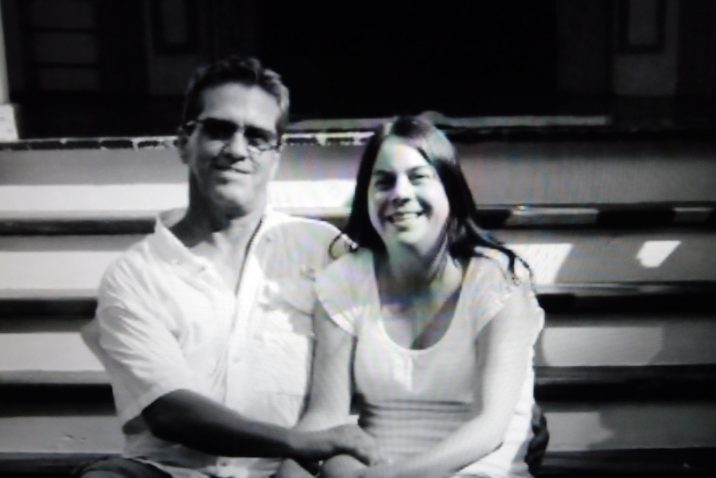

After T.J. was born, Hood said she had never seen her daughter so happy. She was extremely proud of her new family.

“They told me then she was the first in the world that had the Fontan procedure who had a baby, and now her son has babies,” Hood said. “So, she was able to become a grandmother, as well.”

Unfortunately, Hood said, her daughter became pregnant a second time a few years after T.J. was born, but she lost the baby in a miscarriage.

“The second time she got pregnant, that’s when she started having health problems again,” Hood said. “When she lost the second baby, her heart would not stay in a normal sinus rhythm and she started suffering from atrial fibrillation.”

For a little while, Hood said the drug Amiodarone helped control her daughter’s heart rhythm. But eventually, doctors had to use a defibrillator to restore her daughter’s normal heartbeat, she said.

By that time, Hood said her daughter decided to have a procedure called cardiac ablation at another hospital outside of Georgia.

Cardiac ablation is a procedure to scar or destroy tissue in a patient’s heart that is allowing incorrect electrical signals to cause an abnormal heart rhythm. But Hood said there were problems during the surgery and doctors determined she needed a pacemaker.

“After getting the pacemaker, she actually felt much better, but about four years ago, doctors told her she needed another surgery which would basically remove the right atrium,” Hood said. “Angela went through all of the tests and was ready to have the surgery, but then she found out that her son, T.J., and his wife were pregnant. She told the doctors that she wasn’t having surgery until after the baby was born.

“She so loved that baby and was in the room when he was born.”

Once her first grandchild was born, doctors again urged her to have the surgery, but she refused, Hood said.

“Angela later told people that she was not having the surgery because she simply didn’t want to go through another open-heart surgery. She was just tired,” Hood said. “I honestly thought she would get sick and go into the hospital where she could have the surgery and we would have a chance.

“But we did not get that chance. I believe that if she’d had the surgery, she would be here with us today.”

The strength of a mother

Growing up, T.J. Smith said he didn’t realize his mother had a serious heart condition because she never wanted to discuss it.

“Mama never talked about it with anybody,” said Smith, who is now 33 years old. “If I wanted to know anything, I’d have to talk to my step daddy or my grandma. They knew about her health problems. Mama was not going to ever talk about it.”

Instead, Smith said his mother simply wanted to enjoy life and she treated each day as a blessing.

“My mom did exactly what she wanted and if she didn’t get to do it, she was upset,” Smith said, laughing. “She was a very good person to be around. She always wanted everybody to get along and to just live your life the best you could.”

His mother was also determined that he get a good education and behave in school, Smith said.

“She sat down at the table with me every night just to make sure I did every single bit of my homework. And if I didn’t, she’d be mad,” he said. “I mean, we would sometimes sit there for hours and hours, but she wouldn’t move until we got done with it.”

There wasn’t a day that went by that Smith didn’t know how much his mom loved him, he said. But when he learned his mom actually risked her life to give birth to him, their bond became even stronger.

“When I found out, I was like, ‘I am a miracle,’ even though sometimes I don’t feel like it,” Smith said. “But my mom loved me very much. She was my mom, but she was also my friend. I talked to her two or three times a day.”

In fact, on the day his mom passed away in September, Smith said he stopped by to check on her.

“She did a lot for other people and couldn’t say no if anyone needed her help. She was always putting everyone before herself,” Smith said. “So, I kept in touch with her and checked on her all the time. I was actually there when it happened. To this day, I can’t believe she’s gone.”

He only wishes his children had more time with their grandmother.

“It hurts me that she can’t be here to see her grandchildren grow up. That was Mama’s world,” Smith said. “Our son is almost 3 years old and Mama found out before she died that we were having a little girl and that we were going to name her Savannah. She was getting excited and already buying stuff for her. I hate that she’s going to miss out on spending time with them.”

But Smith said he knows his mother is watching after their entire family.

“She’s been giving me signs,” he said. “For months after Mama died, we kept seeing a bunch of yellow butterflies. So, I think she’s there, sending us her love.”

An undying love

As a physician who cared for Angela as a child and followed her through adulthood, Strong said it was difficult to hear of Angela’s death at 54 years old.

“She was always delightful and positive and always had a smile on her face,” he said. “Virtually every time I saw her, her mother had accompanied her to the appointment, even as an adult. It was always a pleasure to see both she and her mom and how they were carrying on. Angela was just a very lively young woman who thoroughly enjoyed life.”

Even though it’s been months since her daughter’s death, Hood said she still expects to see Angela walk through her front door.

“We went everywhere together and talked every day. I don’t know what I’m going to do. I can’t wrap my head around it,” Hood said, as tears rolled down her cheeks. “I feel guilty. I feel like I let my guard down. If I hadn’t let my guard down, I would have gotten her to the hospital.

“I always looked after her before and I knew before anyone else knew that something was wrong. I just didn’t make it this time.”

While her friends and family have insisted there wasn’t anything she could have done to prevent Angela’s death, Hood said the last few months have been hard.

“I had Angela for 54 years, which is a lot longer than I thought I would, but it doesn’t make it any easier,” Hood said. “She meant the world to me and I am grateful for every minute we shared on this earth. No one had anything bad to say about her. Everybody loved her.

“I tell people all the time, ‘I didn’t lose my daughter. I lost an angel.’”

Augusta University

Augusta University